Don't waste time on doubters

Disrupting is best done quietly

I had a conversation with someone this week that crystallized a bunch of separate thoughts for me into a more coherent whole. I think it’s a really useful mindset to have when building anything, but particularly when building something really new. So, let’s go through the ideas.

New and disruptive ideas are, by definition, uncomfortable for people. We’ve talked about that here before. If something challenges your world view, you’ll react negatively to it, and find reasons why it’s not really valid - we call those “why not” stories around here.

The insight though is that that reaction isn’t rational, which it seems to be, but emotional. Even though someone will have what seems like a reasoned, reasonable and rational objection to what you are trying to do, what’s really going on is that they start from the emotion, and find the reason for the emotion, not the other way around. Which means that if you do manage to address their objection, they’ll just find another “reason” to feel the same way - you haven’t addressed the underlying emotion. Once you’re aware of it, this pattern is easy to spot - much of the commentary about AI seems to fit it these days.

That means that time spent arguing with doubters instead of building is purely wasted. Because the underlying emotion isn’t going to change, what you’re doing is futile - you’re just wasting time boxing with shadows. And it’s hard to ignore! People have strong emotions about disruptive ideas, they want to argue with you, not to help your project, but to make themselves feel better. It’s pernicious - you will often get people who seem helpful but who, in fact, are just trying to make themselves feel better and maybe derail you. Unless you are fairly certain you can learn something useful about your project, it’s better to not engage with them at all.

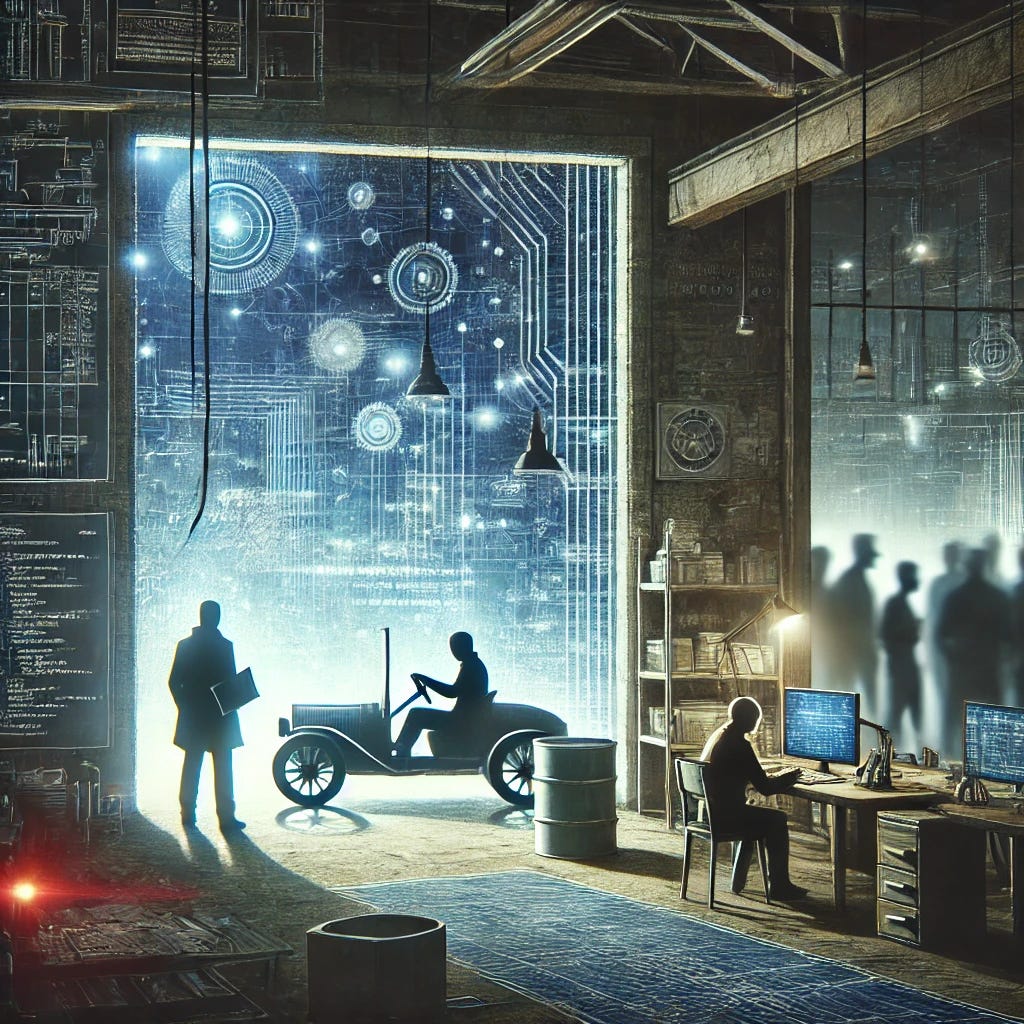

So, the conclusion I came to is that if you are being disruptive, it’s advantageous to be considered irrelevant or be overlooked. At least until what you’ve built is good enough that it doesn’t matter what people think about it. This mentality is harder to pull off as you get more accomplished - you want people to pay attention to what you are doing and what your ideas are (I do, at least!), and so you spend time talking to folks and trying to convince them, instead of building.

Particularly inside of larger organizations, this is dangerous. Getting the attention of someone with the power to kill an innovative project is very easy in a large company. It’s almost always better to be off in a corner somewhere, being ignored. This is also, I think, a common failure mode for corporate lab projects - by calling out and elevating the lab, it invites distraction and bad actors far ahead of when the ideas themselves are ready. It’s usually better in my experience, to quietly sequester the right few engineers in a corner somewhere and let them be creative until they get to the right idea.

This sounds counterintuitive and maybe even anti-social, but it’s a pattern I see over and over. You can’t expect real innovation and disruption to be smoothly accepted by the mass of your culture, no matter how much you talk about it. People come to ideas in their own time, usually when something is really useful to them personally, and when they can tell themselves it was somehow “their idea”. Not fighting this tide is an important part of being a successful inventor.

So much truth in this, and great advice to not waste time trying to convince!

We dedicate a whole pattern chapter in The Insider's Guide to Innovation at Microsoft to leading with emotion. The work done in the Office group to understand that "Think Act Feel" is really feel, act, think was a hard sell when it was first brought out in the company. Now the knowledge of it is apparent in the other case studies.

One tiny but critical edit I would make to what you write above is that engineers should be creating with designers and marketers, lest they waste a lot of time solving the wrong problem or solving the right problem the wrong way. As Julia Liuson said, "Innovation is creating something that changes the customer's life. If you can't significantly change a customer's life, it's not innovation. It's just a cool idea."

This is really helpful. I’ve been struggling with the idea that I need more buy-in before executing when I could have just been executing. A reminder that the best way to persuade people, is to let them persuade themselves.